I spent many years of my childhood searching for the mythical land of Bixlersville. My father used to tell me and my brother and sisters about it all the time, and I roamed the back roads of Egypt, PA sure I would find it sooner or later. Bixlersville was a simple place where people were mostly hard working farmers who lived without modern devices. Dad would go on and on about life there, and even when he told me that my real mother—Sarah Bix—lived there, I didn’t catch that it was all a joke he was playing on me. I think I was about 15 when I finally figured out my dad was pulling my leg, but as it turns out the joke is on him. I have found Bixlersville; it is in Kenya.

Hand made fences dot the landscape in Mukhweya.

Typical road in Mukhweya on way to my host family’s home.

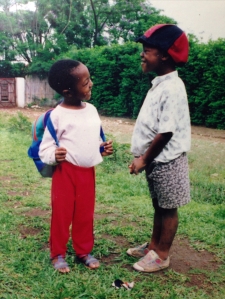

Kids relaxing in compound across the street.

Here is Mama feeding her chickens just outside her kitchen in her Palm Sunday dress. She loves feeding them her precious finger millet–one of the many crops she grows.

The fields, like the sky, go on and on and on and on. This is very fertile soil and the farmers here know how to plant and grow their crops.

The cows do not seem to care that my clothing needs to dry….

Typical home in Mukhweya. This shot was taken just up the road from where I was living.

Downtown Bungoma

Whenever I saw this donkey, I knew we were only about 17 ruts away from home.

Another typical scene.

I am living in a rural area of western Kenya. The nearest big town in Bungoma, but it is a hard to get there. It is almost 30 minutes away on roads that are rutted and difficult to manage. There are children in the village of Mukhweya who rarely, if ever, see town. I am told that Dominic, the 13 year old grandson of my hosts, goes to Bungoma maybe twice a year, and that is because he is lucky; his family owns a vehicle. Not a car, a vehicle. Frankly, I don’t know how any cars could survive these roads. There have been bad roads everywhere in Africa, but here the roads make me dizzy and my stomach churns as we dip and dive into ruts. But I am grateful to have the luxury of transportation and John, the able and kind driver, and I have been become fast friends. He has driven me where I needed to be and waited for me when I had to find a chocolate or Internet connection. He works for my hosts, Mzee Dominic Wetang’ula and his wife, Faustina who have embraced me into their home. My African “mother,” (sorry mom, you know you’re #1) who everyone calls Mama, says I am her last born, and she has named me Susana Naliaka. I arrived at her doorstep at the time of weeding–so I am

Naliaka, the Swahili word for the season of weeding. She has been teaching me Swahili and I’ve made more progress in that language than any other. I even have a little “schtick” that brings down the house–and it’s not my accent. I think everyone is just amazed that a white person can say something somewhat convincingly that indicates I have some connection to their culture no matter how tenuous. It’s been helpful to have some language because in the work I have been doing with Mzee (the title given to those few older men who have earned respect), it’s good to have an opener. In the few short weeks I’ve been here, I’m amazed at all Mzee is doing to get a few steps closer to building the first ever library in all of Bungoma County. Mzee is coordinator of the library committee and just about every other committee in the community. He is sought out by scores of folks for his advice and opinion. Everyday there is a line up of people at the door seeking his assistance. Two of Mzee and Mama’s grandchildren, Nora and Dominic, have been at home because it is school vacation. They work tirelessly doing the farm chores, cleaning, cooking and generally helping with anything their grandparents ask. Sometimes their mother Stella, a hard working woman who has a stall at a local market and reminds me of my Aunt Nancy, stays for a day or two. The whole time she is here, she is in motion. Here, everyone works and everyone relaxes. It is the extreme of both edges in Bungoma.

Mukhweya feels caught in a time warp between the mid-thirties, the early seventies or eighties and the present. There are moments when I feel like my mother and I have switched places. Mom grew up in the village of New Tripoli, PA, at a time when electricity was still new. There is electric here in Mukhweya, but it operates on its own whims, particularly during the rainy season. No one seems to know why, but when it rains, even if there isn’t thunder or lightening, the electricity will disappear for one minute or five or for the rest of the evening. No one blinks an eye. The kerosene lamps are always at the ready just like my mom told me they were in her home. And just like in New Tripoli and the Egypt of my youth, family is right next door. My mom’s extended family and my own cousins all lived within walking distance, and we saw each other on a daily basis. That is how it is here. Everyone in this compound and the one across the street are related…in fact, it seems like most of the town is related to each other. I am living on a compound with three main houses all made of mud and plaster, several smaller houses, and lots of buildings for animals. The dog Jerry (of Tom & Jerry) just had seven puppies under the chicken coop—similar to the way my cat Snowflake insisted on giving birth to her kittens on top of the coal in the cellar bin. Here in the “suburbs” of Bungoma is that deeply rural community where people are connected to the land and each other. I watch the young man who does all the chores bring a headless chicken into the kitchen, and I know about two hours later I will be eating the rest of it. I visit with the widow who has HIV and see how her family around her is taking care of her children. I watch the water porter go back and forth on his bicycle lugging big yellow jugs between the water tower and people’s homes all day long. I see the little girls here bring their coins to church wrapped in a hankie, the same way I did in Egypt. In the evening I sit with my “family” and watch this Spanish show, The Reys, a poorly acted soap opera that seems to have folks here riveted, and I remember sitting with my brother Roy and his wife Cece watching an Emmy Award winning show, Hill Street Blues, after a long day at my first teaching job in Omaha, Nebraska when I was just beginning to learn how to use computers in the classroom. Back in Mukhweya, I glance up from my breakfast and look at the children in the compound effortlessly using my Ipad. Bungoma is at the intersection of modernity and the past, and it is desperately trying to bring itself front and center.

Mama in a rare moment allowing me to photograph her with a smile–probably because she is wearing her church prayer group uniform.

Mzee fielding one of hundreds of calls he receives every day.

Here are Nora and Dominic. This is a sister brother team. Like their mother, they are hard workers. Everyday they are up helping with chores around the house and they don’t stop until nightfall.

Here is John. He drives the vehicle and saved my life several times by being at the right spot with the vehicle just when I needed him most.

This is Stella. She is the mother of Nora and Dominic and she works hard. Every Day.

Sarah and her daughter Joyce live in the compound across the street. I became quite fond of Sarah and she gave me a piece of cloth that says in Swahili, “Give those who love each other more chances to love.”

An impromptu jazz session with homemade instruments on Easter Sunday got the little ones dancing.

Xavier, the general all around farm hand who does just about everything.

The Water Porter. I never caught his name and I don’t know how I got this photo without his trademark hat, but every time I looked at this guy I knew there was a story waiting to be told. He usually has 3 big jugs on his bike and he works from sun up to sun down.

My friend Augustine, who reminds me of my own Pappy Reitz.

Two 3-4 year old boys in compound playing on my Ipad. They figured it out in about 5 minutes. I’m still working on it.

Ostensibly, I am here to assist the library committee establish its first library in this community, but that is a job much bigger than I am. Lindsay Kaplan, a teacher at Waynflete connected me with her sister Eva Kaplan who is the Director and Co-Founder of Maria’s Libraries, a group committed to helping spread the growth of libraries in Kenya. In Bungoma the committee has a vision of a library that serves as a community center and helps promote a reading culture. Many people here have never been to a library, and one member of the committee succinctly stated the vision of the library this way, “In a nutshell this library will be a transformational center for the community in terms of development and will provide a hub of social exposure.” I will not be here to watch as this library takes off, but Maria’s Libraries will be offering advice and has already donated a bicycle so that the library can begin a mobile library until the more permanent library they plan to open in a building donated to the cause is ready to go. Eventually, however, the library hopes to construct their own space. Eva has helped connect the committee to Books for Africa so that a container of books can be shipped from NYC all the way to the door of the new library. Maria’s Libraries sponsors programs for libraries in western Kenya, and I had the opportunity to attend part of a training given for librarians starting a literacy and cultural program called Mama Mtoto. The idea behind this mother and child program is to help instill a love of reading in mothers and their preschool children. The mothers tell stories of their own childhood or culture, and eventually one of the stories becomes a book that is produced in both hard copy and digitized form and shared in the vernacular with libraries in other sites. The very week after the training, Rosemary Imbayi, head teacher at Sigalagala Primary School, was already implementing the program. Rosemary voluntarily began the library at her school and even though school was on vacation, she was in school working with mothers, their preschool children and about 40 K-8 children who came to school to keep reading during vacation. Meeting Rosemary was one of the highlights of my time in Kenya. She is a marvelous human being and in addition to all she does at her school, she is the Commissioner of Girl Scouts in her region and a tireless proponent for the children in her community. You can learn more about folks like Rosemary and the work of Maria’s Libraries at : mariaslibraries.org.

The big surprise of my stay in Kenya was the computer workshop I delivered to a group of almost 30 primary school teachers. That’s right, I was in charge of designing and presenting a training for folks who have little or no experience on the computer. I can just hear the GALES of laughter from my colleagues at Waynflete since despite dutifully attending computer camp for years at the end of school, and trying to stay current with Google Docs, Schoology and whatever else is new on the horizon of technology, my own computer skills leave much to be desired. Fortunately, I had the able assistance of Daniel, the Computer teacher at Luuya Girls’ School who fielded all the really hard questions, and the support of my friend Esther, Head of the School. I did the easy stuff like explain what the on button looks like and how the monitor is the eyes of the computer. Thanks to my buddy Sara Staples and the generous teachers at Portland Adult Education, there were big plans to sign teachers in Kenya up for gmail and give them pen pals with the teachers at PAE, but just as we were about to begin the internet portion of the workshop and Skype with Sara, it started to rain. You remember what I told you about rain and electricity? Well, it didn’t just rain, it poured. There was a deluge and the cows roaming around the schoolyard actually came onto the porch and almost entered the workshop with us. Then the electricity went out and despite having a back up plan of a modem to get the internet (I mean, I am a computer teacher after all. I know about needing a back up plan with technology), the modem didn’t work either. Not to be daunted, we gave out the email addresses of teachers from PAE anyway, and Daniel has promised to meet with any teachers who can come back and want help creating an account.

That’s Rosemary and I on the day I visited her school and met the children (and a few mothers) who all came to school during vacation. Rosemary voluntarily kept the library open so kids would have something to do during the month long break from school.

The Bungoma County Library Committee with the shiny new bicycle Maria’s Libraries donated to them.

Here is a group of Primary School Heads of School who Mzee and I talked to about the upcoming library. I also did a computer training workshop (Yes, you read that correctly, I led a computer training session) with many of them and teachers from primary schools in the area.

That’s one of my new friends Esther. She is the head of Luuya Girls’ School and also the Treasurer of the Library Committee. She is also a lot of fun and was very kind to me.

Students in Rosemary’s classroom/library singing for me.

Proof I actually did do a computer training session. (Can you see the picture of the universal power button on the board?) I had lots of help from the head Computer teacher at Luuya Girls’ school whose help was especially valuable when the electricity went out during the presentation.

It wasn’t all work in Kenya, but I have decided to write a much shorter, more pictorial version of the fun I had in Kenya in an upcoming post. Kenya has been a time of working, learning and remembering. It wasn’t always easy, but it has taught me about the need for time to reflect and given me gratitude for all I have in both my personal and professional life.